This is a multi-part article in which we will cover Migration Endpoints. First, we will cover what Migration Endpoints are, what you use them for and how you can manually configure a migration endpoint. In the second part of this article, we will dive deeper into how you can leverage multiple migration endpoints to potentially speed up your migration to Exchange Online. Lastly, we'll discuss some of the most common mistakes regarding Migration Endpoints and how to avoid or solve them.

Part 1: Migration Endpoints - How they relate to Hybrid Deployments and Migrations

Introduction

One of the key benefits of a hybrid configuration is the near seamless operations between the on-premise Exchange environment and Exchange Online. One of the cornerstone capabilities that unlock this experience is the ability to move mailboxes from on-premise to Exchange online without much hassle like having to recreate a new Outlook profile. Especially since the situation around cross-premise premises permissions are getting better, being able to move mailboxes to and from Exchange Online is key.

As the name implies, Migration Endpoints are ingress points into your on-premises network through which data is moved to Office 365. Exchange Mailbox moves exists in two flavors: push and pull. However, a mailbox move to Office 365 is always a "pull"-type. This means that Exchange Online will make an inbound connection to your on-premises Exchange servers over the (pre-)defined migration endpoint(s). The endpoint Exchange Online uses, it the one you define/select when creating a new move request or migration batch.

By default, the Hybrid Configuration Wizard (HCW) will attempt to create a migration endpoint the first time it runs. This is great for (smaller?) organizations that just want to start migrating mailboxes right after they ran the HCW. In the real world things are a little different. Often, the HCW is ran weeks before the first mailbox is moved. And while I don't necessarily recommend leaving that much time in between, sometimes that's what you must work with.

Typically, a migration endpoint for Mailbox Replication Services (MRS)-based moves consists of the following information:

- The Endpoint Itself: This is the DNS name of the endpoint and must match the certificate presented when the connection is established. For example: endpoint1.exchangelab.be

- A Name: This is the description you will seen when creating a new migration batch/move request from the Exchange Online control panel.

- Credentials*: This is a pre-shared username/password combination that Exchange Online will use to:

- Test/establish the connection

- Migrate the mailboxes to/from Exchange Online

* Note: when the HCW runs, it will attempt to create a migration endpoint based on the Exchange Web Services (EWS) external URL and using the credentials of the logged in user (who is running the HCW). Often this account will have too many privileges in the on-premises organization. From a security perspective, it is better to create a service account which only has the required permissions. In this case: the account must be a member of the default "Recipient Management" role group. An important side note here is that granting the account only the "Recipient Management" role (through a Role Assignment) will not be sufficient. Confusing, I know. There is a role group named "Recipient Management" and similarly named role "Recipient Management". So, don't get confused!

Common Publishing Topology of a Migration Endpoint

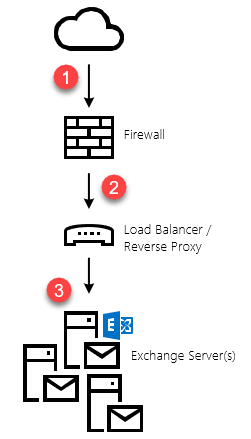

As pointed out in the note above, the default migration endpoint (the one that gets created by the HCW), will be based on your EWS external URL. If you have published your Exchange Web Services externally, then this is likely how it's published to the Internet:

- While the above (logical) representation is common, it does not necessarily have to be the way you configured external publishing for Exchange; if at all. Some organizations have multiple layers of firewalls or have traffic pass through both a Reverse Proxy and Load Balancer (albeit on a different device or virtual instance). Even with all those elements in place, the same logic still applies.The migration fabric in Exchange Online establishes an inbound connection to the migration endpoint (e.g. EWSExternalUrl.domain.com).

- The on-premises firewall translates the incoming connections to a Virtual IP on a Reverse Proxy or Load Balancer.

- The Reverse Proxy / Load Balancer distributes the traffic to one of the underlying Exchange servers.

Improving Performance of a Single Migration Endpoint

Because there are a lot of components at play, the migration performance also referred to as migration velocity can be influenced by a lot of things; some of which you might control, others not. For instance, between your on-premises organization and Exchange Online, there is the Internet. And while you can increase your bandwidth to/from the Internet, you don't always control how traffic is routed to/from Office 365 to your on-premises organization. This is also one of the reasons why Microsoft is putting so much effort in improving the network infrastructure and peering locations on their end. By doing so, they can greatly influence the perceived performance in Office 365. But we're digressing, now.

If you are using a single migration endpoint to move mailboxes to Office 365, the velocity will never exceed the maximum capacity of each link in the chain. In the above topology, that would be:

- The Firewall: Firewalls exists to – often – act as the first barrier between the unknown (the Internet) and the internal network. As such, firewalls have evolved from devices/software that allows/disallows traffic based on the destination IP and port to an eloquent piece of engineering that can apply a vast amount of logic to determine whether a connection is legit and should be allowed or not and should be blocked. Each additional protective feature you activate for inbound traffic will incur a performance penalty on the latter. Depending on the type of firewall, this can delay incoming traffic with many milliseconds. While this might not seem a lot at first, it will hamper your migration throughput.

- The Load Balancer or Reverse Proxy Infrastructure: Often these devices (or virtual instances) can do all sorts of interesting things to traffic. Don't. Like firewalls, this might decrease the overall performance. The same is true when it comes to handling SSL. SSL bridging (decrypt/re-encrypt) is fine. SSL offloading (just decrypting) is not. The MRS Proxy cannot handle unsecured connections. When bridging traffic, you can either reuse the same external certificate, or rely on an internal one. Load balancing itself can also have an impact on migration velocity. If you have setup load balancing for Exchange 2013/2016 following Microsoft's recommendations, you will likely have done so without any (session) affinity. This means that each incoming connection is potentially forwarded to an Exchange server different from the previous one. Although Exchange is perfectly capable of picking up where another server left off, this operation incurs a small overhead (re-establishing a connection with the backend mailbox server). Over the course of a few mailbox moves, this happens potentially hundreds of thousands of times. Many small delays can end up being a big one.

- The (Internet) Connection: It is the most obvious element, but rarely the one that causes a congestion first. If you have a 100Mbps internet connection, know that you will never be able to push more than 12,5MB/sec to the Internet. Of course, not all is black or white. Some organizations have so-called "burstable" connections. For instance, they could have a 100Mbps connection, burstable to 500Mbps (with certain limitations). In case of the latter, you could theoretically push up to 62,5MB per second for short periods of time. The same logic applies to the network connectivity. If you have a 1GB network connection, internally, then you won't be able to push more than 125MB per second. In reality, however, top speeds are always lower than the theoretical maximum.

- The Back-End Exchange Infrastructure: Often this is the n°1 reason why migration performance is not up to the levels one might expect or hope. Ultimately, a mailbox move is nothing more than an Exchange server reading from disk and passing on traffic to Exchange Online through the MRS. However, if your Exchange servers are (too) busy with normal operations, they will have little resources left to handle mailbox moves and thus slow down the overall process.

To minimize the impact of any of the above, consider doing all (or some) of the following:

- Avoid enabling additional/unnecessary traffic inspection or filtering. Although traffic might be hitting your Exchange Web Services endpoint, it must authenticate first before being able to move data out of your organization into Office 365. As such, the default DDOS-protection features, and basic firewall filtering should suffice. No traffic inspection is required. The same is true for your Reverse Proxy: just let it forward traffic onto the Exchange servers without much ado.

- Avoid having to go through too many networking devices. Each hop along the way will increase the latency of the connection.

- Make sure your on-premises Exchange servers are healthy and performing well. Especially the latter is important. Although no additional infrastructure is required, moving mailboxes adds a (small) overhead on your on-premises servers. Making sure that you've got plenty of CPU cycles and disk IO available is a good start!

- If possible, do not load balance traffic to/from the MRS Proxy (on the EWS endpoint); just virtually tie-up a single backend Exchange server to a single external migration endpoint. This approach will be discussed in more detail in part two.

In addition to these "external" factors, there are a few other things you can tweak to improve performance. On the migration endpoint itself, there are two values that can be changed:

- MaxConcurrentMigrations denotes how many mailboxes can concurrently be moved from the migration endpoint during the initial phase of the migration (copy of the mailbox). The default value is 20.

- MaxConcurrentIncrementalSyncs depicts how many delta synchronizations can be active at the same time. The value for the default endpoint is 20. When you create a new endpoint, the default is 10.

The values for each migration endpoint can be modified using Exchange Online PowerShell and the Set-MigrationEndpoint cmdlet. Although you can create as many migration endpoints as you would like, you can only configure a maximum of 300 concurrent migrations over all the existing endpoints. This value can be retrieved using the Get-MigrationConfig cmdlet:

PS C:\> Get-MigrationConfig | fl

RunspaceId : b9953935-cd81-4ec7-a263-cc55879210f5

Identity : tenantname.onmicrosoft.com

MaxNumberOfBatches : 100

MaxConcurrentMigrations : 300

Features : MultiBatch, PAW

CanSubmitNewBatch : True

SupportsCutover : False

IsValid : True

ObjectState : Unchanged

Although 300 should be sufficient for most organizations, you can request support to raise this value to as much as 1000. Please note, however, that it is far more likely you will run into performance bottlenecks elsewhere before hitting the 1000 concurrent migration limit.

Slow migration performance is rarely caused by a lack of resources on Microsoft's end (though it happens). Most of the time, I see a lack of performance at the source side, like ill-performing Exchange Servers, badly configured networking devices etc. However, if your base infrastructure can handle the load and you're not getting the performance you wanted (or have guestimated), tweaking the endpoint and MRS settings might be a good starting point. In part two of this article, we'll investigate how you can scale out using multiple migration endpoints.

Next Week - Part 2: Using Multiple Migration Endpoints to Speed Up Migrations to Exchange Online