Microsoft Exchange Server SE . . . the final version of Exchange?

Microsoft announced the next – or last? version– of Microsoft Exchange Server. Customers and...

Securing Exchange as part of a larger security framework

Microsoft Exchange installations may have lessened dramatically with the advent of Exchange Online, however - Exchange Server is still deployed at such a massive scale within some environments to the extent that customers feel like they either cannot, or will not, make a complete move to Microsoft 365 cloud services.

In that context, securing on-premises Exchange becomes paramount, as the security and stability of Exchange Server directly impacts other areas of your infrastructure. Therefore, the areas that Exchange is dependent on, which we detail in this blog as ‘functional areas,’ must be addressed as part of securing Exchange Server and not vice versa.

It has been an eventful time for Microsoft Exchange Server administrators keeping these servers up to date since the dawn of the decade when multiple Remote Code Execution Vulnerabilities (RCE) were first discovered. RCEs allow attackers to gain arbitrary access to, and then execute arbitrary commands. If your Exchange 2013, 2016 or 2019 servers are not patched and expose port 443 to the internet without an intermediary of any sort, then stop reading this article RIGHT NOW and patch those servers! Patching servers is a large part of what this article will cover, however if your patches are completely up to date, top up your beverage of choice and read on.

This is the first article in a series that will focus on securing Exchange Server, providing practical information for administrators beyond just Exchange Server versioning and patching, and details some of the ways in which we can secure Microsoft Exchange Server using Zero Trust Principles. A critical point to note is that often we own the technologies required to implement a level of basic trust security, meaning we don’t need to rush out and buy a vendor-aligned solution to be “Zero Trust Compliant.”

It’s also important to note that Zero Trust Principles move us away entirely from the previous paradigm of “trust but verify,” creating a defensive posture against internal and external audiences. The practical outworking of Zero Trust is based on the rule that internal networks should have the same amount of trust, or lack of trust, as the internet does, therefore we secure Exchange and the things it touches accordingly. We will define what Zero Trust is, and what it isn’t in the context of email security and walk through the steps required to secure our email infrastructure.

Zero Trust is a set of three principles that define whether or not ‘no user or device is trusted,’ even if either of those are found inside or outside of a corporate network. You may argue that this is yet another framework, but it isn’t. These three security principles, once we adopt them, drive all our resulting processes and behaviors:

As technologists, we assume that we start with the implementation of technology, however this is where we are placing the cart before the horse. Zero Trust Adoption starts with the definition of what actions or permissions you allow, when you allow it and on which resources. The policy defines the enforcement of the least number of privileges needed to perform a given task, while verifying explicitly (we don’t trust but verify) and assuming that we are defending humans and assets from breach.

The definition is summarized into a Zero Trust Policy, which then drives technology implementation decisions. As the Exchange administrator, you want to know where Exchange fits into this policy as part of securing your larger estate.

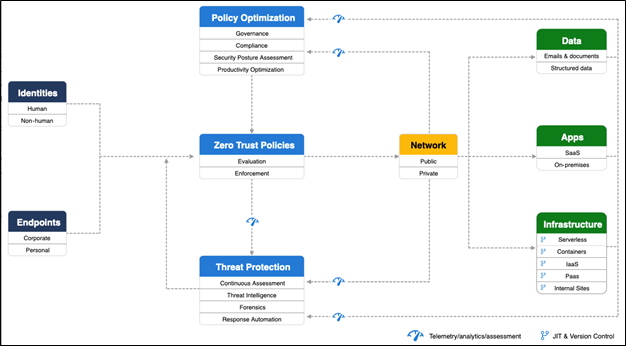

Figure 1 - Zero Trust Functional Areas below captures the placement of how a Zero Trust policy relative to other functional areas that affect Exchange services:

This diagram creates functional areas so we can summarize and focus our efforts, as each functional area defines a policy requirement. Most of these will share a relationship with each other, for example, it is difficult to separate identities from endpoints, and endpoints from data, etc.

Below are some specific examples of how you can define a Zero Trust policy for a given area. Note that these are not meant to be exhaustive, merely examples of the application of Zero Trust principles:

Identity - Human and non-human identities, including devices, service accounts. To access Exchange services, you require authenticated access - Username and password with a second factor. You may want to define which networks/locations may authenticate and when. End-user and administrator definitions are required.

Endpoints - Windows, MacOS, IOS and Android, amongst other endpoints. To access Exchange services, endpoints must meet a minimum standard of current OS and patch levels, along with potential compliance parameters such as non-jailbroken devices, EDR and/or AV versions, etc.

Apps – The presentation or client layer, including Outlook, Outlook mobile, web clients, applications consuming email, etc. To access data held on Exchange services, or to administrate Exchange services, minimum versions of Outlook, Outlook mobile, browser and PowerShell are required. Administration may only occur from known networks, using identities to whom the least possible administration rights have been granted for the minimum amount of time. Client apps may access Exchange data from expected locations, congruent with the business’s expected locations from doing business.

Data – Data at rest and in motion. Exchange data must be encrypted in transit or at rest, irrespective of its location. Server data must be held on encrypted volumes. Mobile OS’s must encrypt the storage locations used by Outlook mobile by default. MacOS and Windows volumes must deploy FileVault and Bitlocker respectively on endpoints storing offline email data.

Infrastructure – Physical and virtual machines, backup and DR infrastructure, etc, Exchange Server and Windows Operating systems must use a supported version and must be patched to minimum levels. Server hardware must be in support and able to support Exchange minimum or scoped requirements. Virtualization platforms must be in support and feature support for the Windows Operating system used by Exchange Server.

Network – The internal and external paths along with email flow, between servers, endpoints and even infrastructure – including backup and DR infrastructure. Internal and external networks must be defined for client and server traffic. These locations also define the kind of operations allowable, for example backup traffic only on the backup network, client traffic via internet, VPN, or internal network ranged and not from server networks, etc.

As an Exchange administrator, or the owner of messaging services, you may wonder why we should care about compliance in an article about Exchange. Exchange is certainly part of a larger ecosystem, containing Active directory, networks, and other infrastructure. What we care about in this section is that “secure” does not mean “compliant,” and compliant does not mean secure.

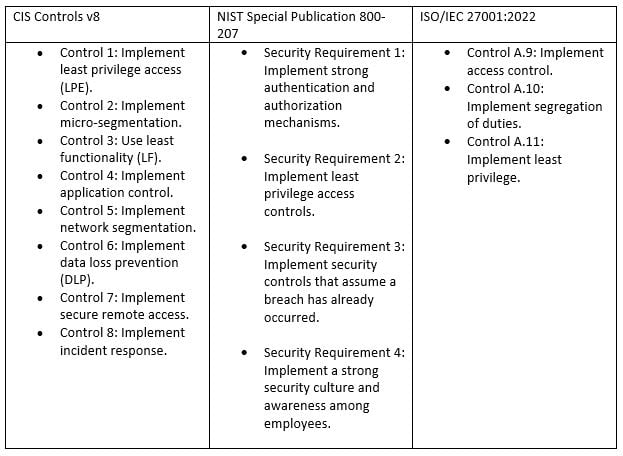

However, there is a large overlap between the two. Adopting Zero Trust as part of securing Exchange may automatically satisfy compliance controls you need to pass an audit, or even to adopt a security framework such as CIS. Zero Trust principles are adopted by frameworks such as CIS Controls v8, NIST SP 800-207, ISO27001:2022 and others.

As I mentioned above, if you work in a regulated industry and wish to implement Zero Trust, you may be happy to note that overlap exists between frameworks, which make Zero Trust complementary to your efforts of securing Exchange.

I summarized some of the overlap on the frameworks relating to Zero Trust Principles in the table below:

You may consider the policy items above and think that Zero Trust is too much effort to implement or maintain. Consider that cost or effort, against the amount of work required to completely recover from a successful breach such as a ransomware attack or data leak. Implementing Zero Trust certainly has a cost, however, the primary reason to implement it is to defend ourselves from an increasingly hostile and opportunistic landscape. Even a basic level of consistent implementation, raises attacker friction to the point where you may no longer be an opportunistic target.

Once we have defined policy items, we move onto the technical implementation of each item. In our next article we define where to start with securing identities to access on-premises Exchange, considering both Microsoft Active Directory and Microsoft Entra ID, formerly known as Microsoft Azure Active Directory.

Do you have numerous Exchange servers that need to be patched? Understanding the version and patch you are currently running enables you to access the security risk in your environment and ensure the patch was successfully installed. The Exchange version report simply returns back the information needed to understand what version your servers are running and if the security patch was successful. (PS - don’t forget to reboot your server after applying the patch!)

Nicolas is the founder, as well an architect, author and speaker focused on Office 365 and Azure at NBConsult. Nicolas is a Microsoft Certified Master for Exchange and Office 365, Microsoft MVP (Most Valuable Professional) for Microsoft Office Apps and Services since March 2007. Nicolas has co-authored “Microsoft Exchange Server 2013: Design, Deploy and Deliver an Enterprise Messaging Solution”, published by Sybex.

Microsoft announced the next – or last? version– of Microsoft Exchange Server. Customers and...

On October 11, 2022, Microsoft unexpectedly released new Security Updates (SUs) for Exchange 2013...